Perhaps you’ve been to a talk on immigration that emphasized that every journey has two ends. True. It also has a middle, and the experience en route may be more memorable. The weather is part of that, especially if the journey was by ship.

Warning: This post may get further into the meteorological weeds than you care to venture. It does demonstrate some of the resources helpful in determining the comfort, or lack of it, your ancestor had in travelling to Canada across the Atlantic.

The White Star Line’s S.S. Doric left Liverpool on 6 December 1924 via Cobh (Cork) bound for Halifax and New York. Matilda, among 120 passengers who arrived to disembark in Halifax early on Sunday, 14 December, recalled.

“We were not allowed on deck for the entire voyage due to weather conditions.”

Rough December seas are no surprise in the North Atlantic. How typical would no access at all to the deck be at that time of year?

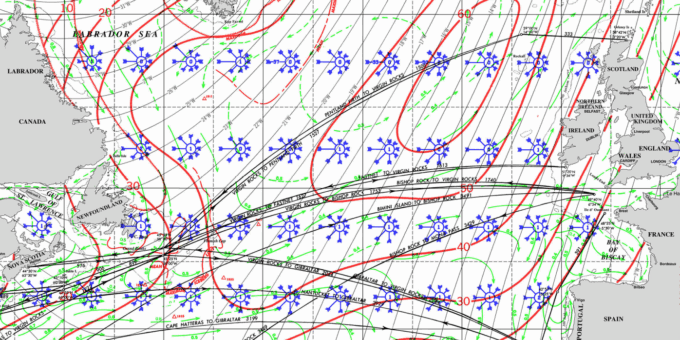

The red lines on this December pilot chart of the North Atlantic indicate the percentage of time a vessel would encounter waves equal to or greater than 12 feet. It’s for perhaps 30 percent of the Doric’s Atlantic crossing if following a Great Circle route. Waves of 12 feet are typical of Beaufort Force 6.

Many ships kept meteorological logs. I checked with the British Meteorological Office, where ships with British registration would have returned a meteorological log.

They had nothing for that voyage of the Doric.

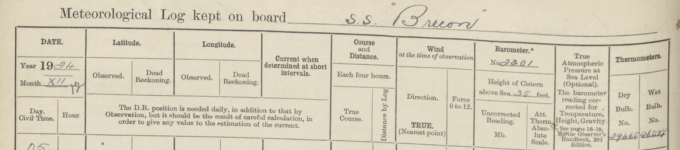

They did have logs for three ships, the Brecon, the Bolingbroke and the Digby that appeared to partially overlap the assumed route and time. The Brecon seems to be the best fit, but we don’t know how far the Doric might have deviated from the Brecon’s route. Here’s an extract from the SS Brecon meteorological log.

The column Force, under Wind, shows a period on the 7th and 8th when the Beaufort Wind Force was 6 or greater. One report, at the end of the day on the 7th, had Force 10, “characterized by very high waves with long overhanging crests, large patches of foam blown along the wind direction, and significant sea spray, leading to reduced visibility. Winds at this level typically range from 48 to 55 knots (55-63 mph, 88-101 km/h). At sea, the sea surface appears white due to the abundance of foam and spray, and the tumbling of the sea becomes heavy and impactful.”

The Course at the time was “various”; likely attempting to adjust to changing conditions.

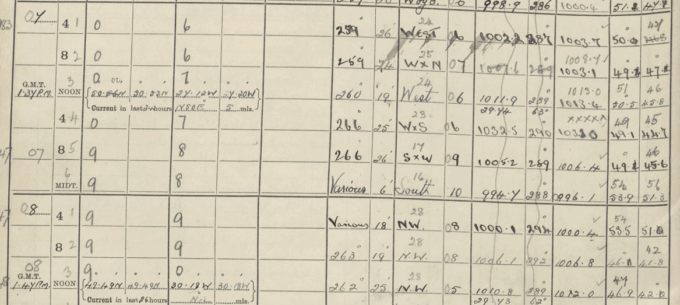

Another perspective on conditions is from a collection of Northern Hemisphere weather maps from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The extract below is for 10 December 2024 at 13 GMT. From personal experience, don’t put a lot of faith in the details. The ship reports are scattered. There’s room for imaginative interpolation in between the ship reports.

The area to the south and east of a low-pressure system generally has the strongest winds, which, combined with the long fetch, the length of water over which a given wind has blown without obstruction, builds wave heights.

A succession of low-pressure systems moving from the west suggests the pause between systems would only be brief.

In summary, the great circle route from near Ireland (at 53.4°N, 7.5°W ) to Halifax, Nova Scotia (44.65°N, 63.59°W ), overlaps the region south of Iceland and between Newfoundland and the British Isles, explicitly identified as having the greatest frequencies of high waves. Ships traversing the area would spend a considerable portion of their voyage with problematic average conditions, maintained by successive storm systems. The Brecon’s log shows that severe conditions were occurring at the time.

Given the evidence available, a prudent captain like Samuel Bolton, who had recently assumed the role for the Doric, might well close the deck to passengers, even between storms.

An excellent article, John. I presume that if you know your ship’s name, you can access her meteorological log, provided she was British and the logs, kept and existing (British Meteorological Office, where ships with British registration would have returned a meteorological log). Do meteorological records for ships of other flags exist?

John, this is a fascinating post and thank you for sharing your meteorological knowledge. This adds context to what the passage from Ireland to Canada might have been like.